This is the text of the first of a series of talks for Lent 2017, given in the the Parish Church of St Peter & St Paul, Lufton

I’ve entitled this series of talks Hymns and the Faith. In each of the talks we’ll look at one or more hymns to see what we can learn from them about the history of singing hymns in church, and also about what singing hymns can teach about God, about Jesus and about the teachings of the Christian faith.

This first talk I’ve called As pants the hart. The hymn was published in 1696 in the New Version of the Psalms of David in Metre by Nahum Tate and Nicholas Brady. It is, of course, a metrical version of Psalm 42. The original version was much longer than the version we find in our modern hymn books which have only three verses from Tate and Brady’s hymn and a doxology added.

It is a straightforward matter to print this hymn and the original version of the psalm side by side and to see how closely the two versions match each other. (see here)

The use of the psalms in Christian worship has a history as long as Christianity itself. Indeed, Jesus himself sang the psalms as we hear in Matthew 26.30, After the psalms had been sung they left for the Mount of Olives. And he quoted from the psalms on the cross and at other times. There are 11 quotes from the psalms made by Jesus in the gospels (from Psalms 8, 22, 35, 41, 69, 78, 82, 110 and 118). The psalms are widely quoted by Paul and throughout the New Testament. It is clear that the psalms were a significant influence on the early Christians, and as many of them were Jews it would be surprising had they not made use of the psalms in their worship, Let the Word of Christ, in all its richness, find a home with you. Teach each other, and advise each other, in all wisdom. With gratitude in your hearts sing psalms and hymns and inspired songs to God (Colossians 3.16).

Initially the psalms would have been sung in the original Hebrew, but as Christianity spread throughout the Roman Empire Christians who spoke Greek would have used the Greek translation of the psalms as found in the Septuagint and, no doubt would have sung them in the Greek style rather than using the traditional Hebrew chants.

After the time of the apostles the Christians continued to sing psalms, and other biblical texts in their worship, and even hymns composed especially by Christians, as Tertullian (160-225) attests in his Apology, 39.16. Each is asked to stand forth and sing, as he can, a hymn to God, either one from the holy Scriptures or one of his own composing…

As the Church’s worship became more formalised the psalms were used in the worship of the new monasteries. Saint Jerome (348-420) records, In the cottage of Christ [the monastery] all is simple and rustic: and except for the chanting of psalms there is complete silence. Wherever one turns the labourer at his plough sings Alleluia, the toiling mower cheers himself with psalms, and the vine-dresser while he prunes his vine sings one of the songs of David.

And as the Church produced the Liturgy of the Hours to shape the monastic life of prayer so the psalms were formally incorporated into it and the whole psalter was sung every week, requiring several hours a day to be spent in worship. Modern versions of the Daily Office still have the psalms recited, although less intensively. In the Daily Prayer of the Roman Catholic Church the cycle lasts a month, as it does in the Book of Common Prayer Psalter. The Daily Prayer of the Church of England found in Common Worship has a seven week cycle.

The psalms then have formed a major focus for Christian worship from the earliest days until today. Hymns, as we know them though, were not widely used in the Church worship until the time of the Reformation and beyond. The one exception to that being the Office Hymns which were sung at the Monastic Offices from the time of Saint Ambrose (340-397). More about those on another occasion.

Hymns, in the modern sense, may not have been very apparent in worship, but they were nonetheless sung by Christians. Perhaps in the early centuries of Christianity hymns were rather more like folk songs than liturgical music. Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430), in his Confessions, tells the story of his conversion. He relates how one day, I heard from a neighbouring house a voice, as of boy or girl, I know not, chanting, and oft repeating, “Take up and read; Take up and read. ” Instantly, my countenance altered, I began to think most intently whether children were wont in any kind of play to sing such words: nor could I remember ever to have heard the like. So checking the torrent of my tears, I arose; interpreting it to be no other than a command from God to open the book, and read the first chapter I should find (Confessions, Book VIII). It is not certain, but neither is it impossible, that these are the words of a popular hymn of the day.

In its early centuries the Church struggled with establishing its doctrine and there were great disputes until the doctrines were settled by the Councils of Nicaea, Constantinople and others in the 4th century. By no means the only dispute, but perhaps the most challenging, was the dispute with the Arians. Arius (c. 250-336) led a movement which emphasized the divinity of the Father over the Son. Arius and his followers were banned from the churches. They took to open air meetings and wrote hymns the words of which which taught their teachings to the believers and to those who might hear them.

One of his hymns included the verse,

There was once when he was not

He was made and not begot

So hang this sign on the weeping willow tree:

There was once when he was not!

In response Christian teachers wrote their own hymns which were also sung outside of the churches. It is said that the Christians and the Arians sometimes, having crossed paths, tried to out-sing the others.

So it was, until the Reformation, that with few exceptions hymns were sung outside of the churches rather than as part of the worship. Other than that it was psalms and canticles, such as Benedictus or Magnificat, that were sung in church.

At the Reformation some of the key figures took differing views about the place of hymns in worship. Martin Luther (1483-1546) and the Lutherans, used hymns extensively for teaching, for pastoral reasons and in worship. Lutheranism has produced great numbers of hymns, many of which are still found in our hymn books today – but more of that on another occasion.

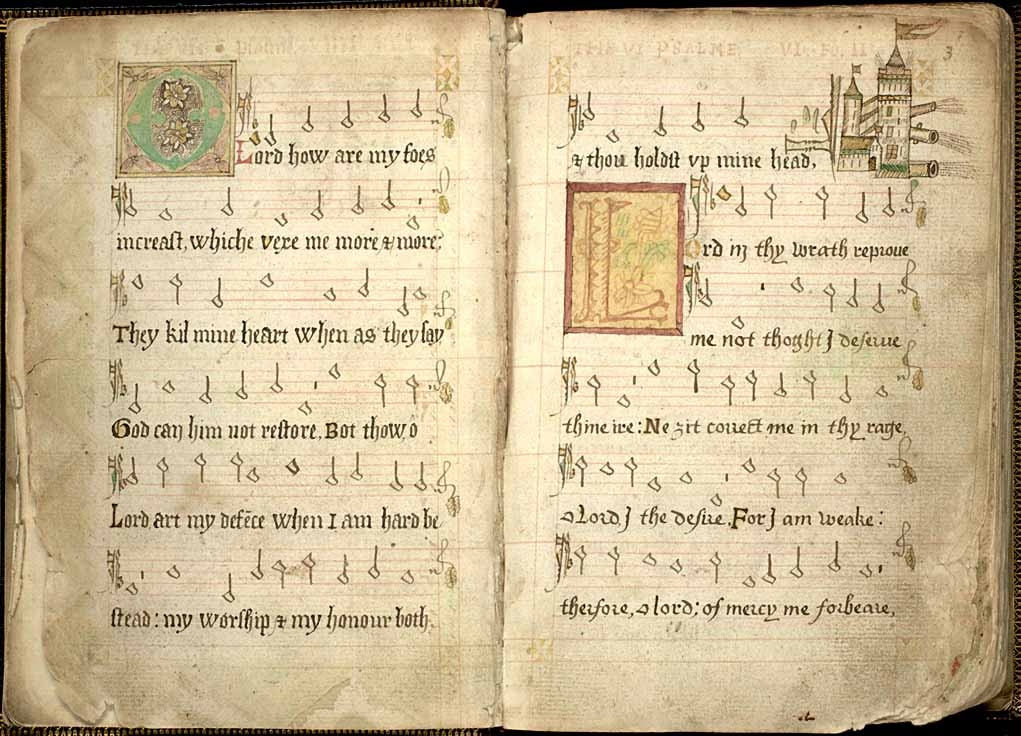

John Calvin (1509-1564) and the Calvinists took a different view. Such was his view of the primacy of scripture for teaching that the only singing he permitted in worship was the singing of psalms. It was largely the Calvinists who were the catalyst for the writing of metrical psalms, such as As pants the hart. All 150 psalms were given metrical versions. Metrical psalters were produced in French, German and Dutch, as well as English.

The first complete metrical psalter in English was The Psalter of Dauid newely translated into Englysh metre in such sort that it maye the more decently, and wyth more delyte of the mynde, be reade and songe of al men by Robert Crowley (c 1517-1588), printed in 1549, coincidentally the year of the publication of the first Book of Common Prayer.

Thomas Sternhold and John Hopkins put forty four psalms into metrical form, published in 1547. Other authors added to these and in due course the whole psalter was published in 1562 as The Whole Booke of Psalmes, Collected into English Meter. One psalm from this collection has survived in use today – All people that on earth do dwell.

Later English metrical psalters include The Bay Psalm Book (1640) the first book published in the British colonies in North America and Tate and Brady’s New Version of the Psalms of David in Metre (1696).

Few of the metrical psalms in these collections have continued in use to the present day. A look at the versions of Psalm 24 from each of them shows why that is the case (see here). Psalms that continue still include,

All people that on earth do dwell

As pants the hart (Tate and Brady)

Through all the changing scenes of life (Tate and Brady)

The God of love my shepherd is (George Herbert)

The Lord’s my shepherd (The Scottish Psalter, 1650)

The Episcopal Church in the USA still publishes a book of metrical psalms, but generally speaking the fashion for a metrical psalter has died out. Which does not mean that psalms no longer inspire our hymnody. A few examples, but there are many more.

As the deer pants for the water (Psalm 42)

Let us with a gladsome mind (Psalm 136)

Praise, my, soul the King of heaven (Psalm 103)

Jesus shall reign where’er the sun (Psalm 19.4-6)

The King of love my shepherd is (Psalm 23)

and many more.

Although the psalms continue to play an important part in our worship to this day, limiting ourselves to only psalms is ultimately less than satisfactory. By the seventeenth century it became clear that more was needed, that a specifically Christian body of sung praise and worship, based on the New Testament, and contemporary experience, as well as the Old, was required. Next time we’ll look at how Christian hymnody developed as the great Lutheran, Methodist and Evangelical hymn writers found a voice and a style.

Read Talk 2 here.

Thankyou, glad I could read that even though I could not be with you