This is the text of a sermon preached on Sunday 18th January 2026 at the Church of St Wyllow, Lanteglos by Fowey, Cornwall

Isaiah 491-7 1Corinthians 11-9 John 129-42

Look, there is the lamb of God that takes away the sin of the world.

I have seen and I testify that he is the Chosen One of God.

Look, there is the lamb of God.

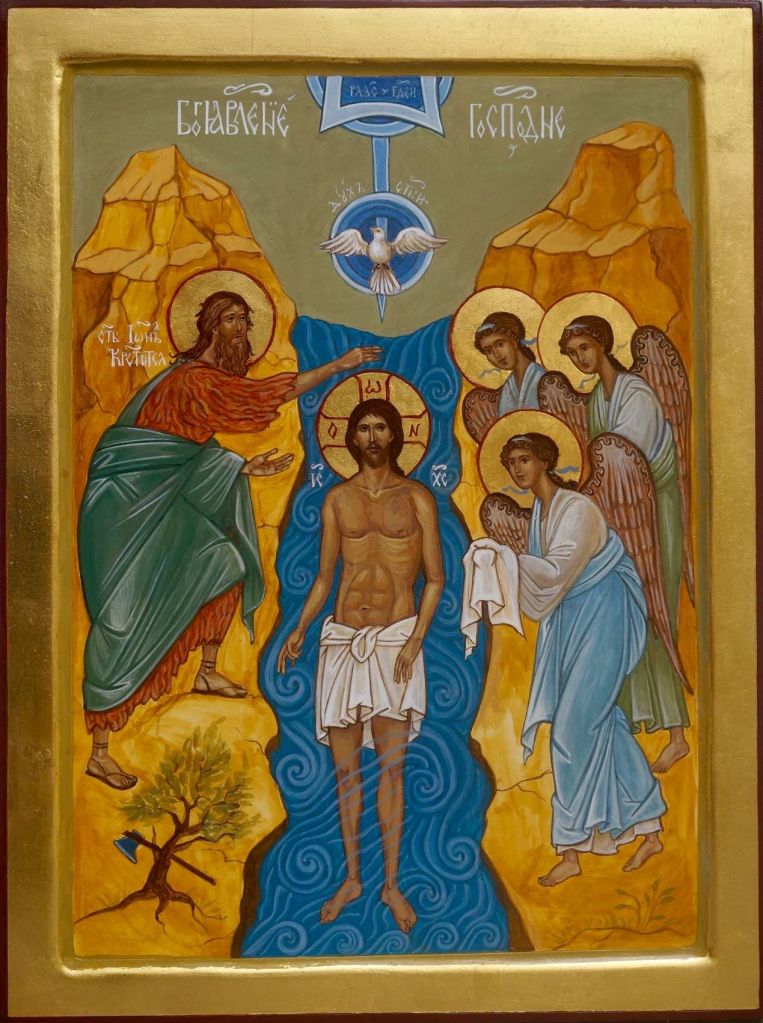

Three things that John the Baptist says about Jesus to his disciples in this morning’s gospel reading. In what he says he uses two of the titles of Jesus that are applied to him in the New Testament – Lamb of God and the Chosen One of God (in the second case some of the original Greek texts have Son of God rather than Chosen One of God).

These are just two of the many titles applied to Jesus – Lord, Master, Rabbi, Son of God, Son of Man, Lamb of God, Son of David, Logos, Messiah – there are others.

Some of them Jesus uses of himself, some are used by others.

When John uses them here they are intended to draw his disciples’ attention to Jesus. They are spoken as a witness.

The previous day John had told the priests and Levites who had come to question him about who he was that he was not the Christ, or Elijah, or the Prophet, and that there was another to come after him whose sandal strap he was not fit to undo.

And now as he sees Jesus coming towards him. Look, he says to his disciples, there is the lamb of God that takes away the sin of the world.

John points away from himself and towards Jesus. The principal role of John the Baptist in John’s gospel is not as a baptiser but as a witness. Indeed, in this gospel the baptism of Jesus is not recorded at all. What is recorded is John’s witness. This is what he came to do – point the way to Jesus.

And very effective he is. Immediately two of John’s disciples go after Jesus and spend the day with him, as a result of which one of them, Andrew, finds his brother Simon Peter and tells him, We have found the Messiah.

Andrew takes Simon to Jesus, who says to him, You are Simon son of John, you are to be called Cephas (which in Hebrew means Rock. In Greek it is Petros or Peter).

In the few verses following our reading the next day Jesus, meeting Philip, calls him to, Follow me. Philip fetches Nathanael and tells him that Jesus is the one written about by Moses and the prophets. When told that he is Jesus, son of Joseph, from Nazareth. Nathanael expresses surprise that anything good could come from Nazareth, but after meeting Jesus and being told by Jesus that he had seen him under a fig tree replies, Rabbi, you are the Son of God, you are the king of Israel.

In just a few verses of John’s gospel we have heard Jesus given the titles, Rabbi, Messiah, Lamb of God, Chosen One of God, Son of Joseph, Son of God and the king of Israel.

Clearly, to each of the characters here who use a title for Jesus that title is significant to them. These titles mean something important for them.

So important are these titles that they are the means by which they tell other people about Jesus. They immediately give others a clear sense of who Jesus is and why he is important.

They use the titles as a means of witnessing to Jesus.

All of which begs the question, Who is Jesus to us?

This was a question that Jesus asked his disciples (Matthew 1613), Who do people say the Son of man is? And when they answer he asks them, more pointedly, Who do you say I am?

We all need to ask ourselves, Who do I say Jesus is?

It’s a crucial question with a crucial answer. And it is a question that no one else can answer for us. Each of us has to answer that question for ourselves. Why is Jesus important to me?

And in our answer we might use one of the titles from the New Testament – Master, Lord, Teacher, Saviour, Son of God.

But there is a good chance that we will want to use a title, or a phrase, of our own – the One who answers my prayers; he teaches me the right way to live; he forgives me and shows me how to forgive; he is the one who challenges me to be a better person; he sacrificed himself on the cross for me.

There are many things we could say about him. You’ll have your own ideas. Your ways in which he has touched your life and transformed it.

That is what makes us a Christian – recognising in Jesus someone who touches and transforms our life by the ways in which he has answered our prayers; by the way he challenges us to review our life; by the manner in which he shows us the way to walk in life; by the way he opens up for us the reality of eternal life – even if we aren’t always clear what that means.

For each of us it is the way that he has touched our life that will dictate how we see him.

And how we see him will affect what title we will apply to him. And for us those titles will matter – in just the way they mattered to John and Andrew and Nathanael because they speak of what he does for us.

They also matter because they give us a way of speaking about him to other people. And because we are then speaking from experience and our witness, like that of John, or Andrew will be all the more compelling because it will be genuine – we will be speaking of what we know rather than simply saying what we’ve been told.

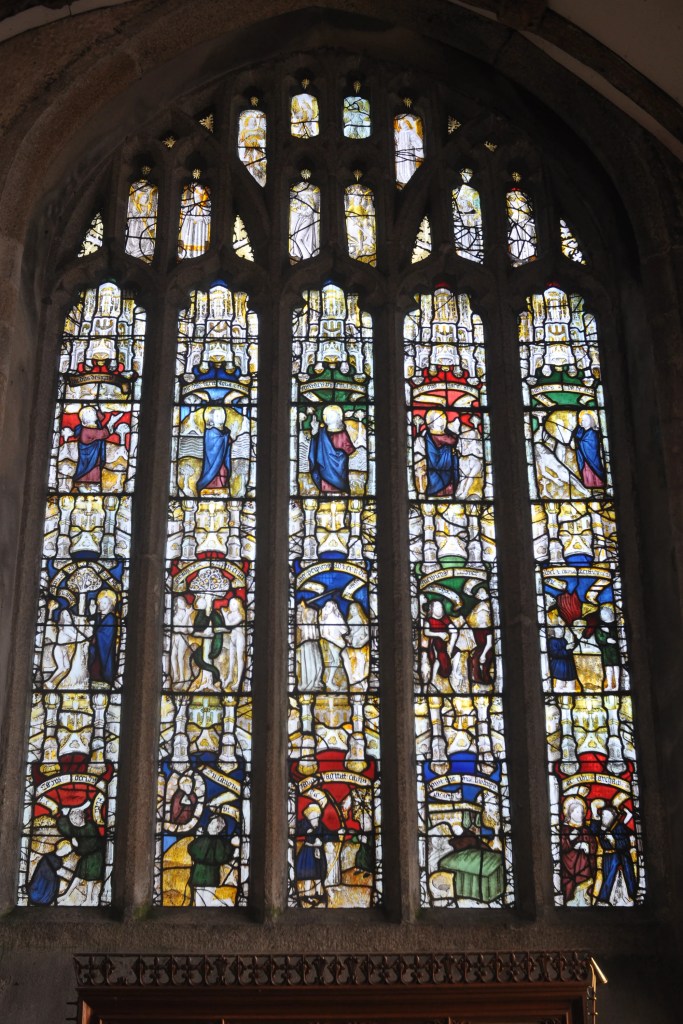

The traditional titles of Jesus are important because they speak of the experience of the Church across the centuries, but the titles we give him today speak vitally of our own personal experience.

As an example: to say Jesus is Lord to a person who has no experience of him could well be meaningless to someone whose only experience of a lord brings up an image from the TV of an old codger dozing on the red benches of the House of Lords.

But to speak of the way in which Jesus has answered your prayer or made you a better person might elicit a more positive response.

The Lordship of Jesus could make more sense into the future.

Jesus comes to us and touches our lives in many different ways – and it is the ways in which he affects us that will give us ways to name him and to witness to him.

Jesus says to us time and again, Who do you say I am?